By James Lawrence, Partner, and Isabella Boag Taylor, Law Graduate

The NRMA has failed on all counts in its Federal Court action to restrain the CFMMEU from using a similar logo and making statements about the NRMA during an industrial dispute about the NRMA’s My Fast Ferry business.

Facts

The Maritime Union of Australia (MUA), as part of the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (CFMMEU), has been involved in an industrial dispute since 2018 with the National Roads and Motorists’ Association Limited (NRMA) over the wages and working conditions of staff on NRMA-owned ferries.[1]

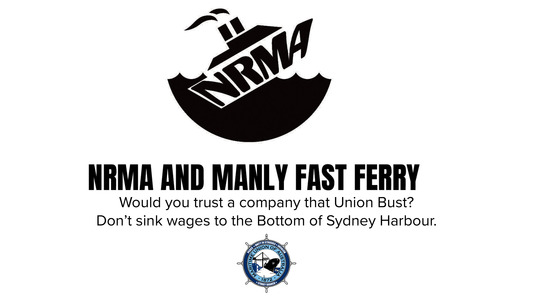

The dispute involved a campaign run by the MUA which used an image of a sinking ship bearing the letters “NRMA,” (the offending logo)[2] which was accompanied by the words “Don’t let wages sink to the bottom of Sydney Harbour.”[3]

|

|

The offending logo was displayed on pamphlets criticising the NRMA which were handed out by the MUA at the NRMA’s Annual General Meeting.[4] The offending logo also appeared on placards, additional pamphlets, and T-shirts worn by MUA members in further industrial action.

The NRMA commenced proceedings against the CFMMEU in the Federal Court on the following bases:

- The MUA had infringed a number of the NRMA’s registered trade marks (both word and device marks) pursuant to sections 120(1) and 120(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (Trade Marks Act);[5]

- The MUA had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in violation of Section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law;[6] and

- The MUA committed the tort of injurious falsehood against the NRMA.[7]

Trade mark infringement

Griffiths J accepted that for the purposes of sections 120(1) and 120(3) of the Trade Marks Act, the offending logo was deceptively similar to a number of the NRMA’s registered marks.[8]

However, his Honour held that the offending logo was not being used by the MUA as a trade mark or badge of origin. The industrial campaign for which the offending logo was used could not be considered the provision of a service by the MUA to its members, as argued by the NRMA. In his Honour’s opinion, the MUA is not a business, does not have a trade, and regardless of this, any MUA activities are engaged in by members, for members, as “functionally, the members are the Union.“[9]

Further, for infringement to be made out the NRMA had to demonstrate that the signs were used in the same or similar class of goods or services.[10] In this regard, his Honour found that the MUA’s use of the offending logo for an industrial campaign directed at wage and condition improvement was not in the same class of ‘services’ as the NRMA’s word mark, which is registered for the provision of information about journeys.[11] The MUA’s conduct did satisfy the elements of subsection 120(3)(b) (that provision being concerned with well-known marks), which requires that the offending logo be used in conjunction with different goods and services to those classes of goods and services in which the NRMA’s trade marks are registered.

Despite this, the NRMA failed to satisfy subsection 120(3)(c), which requires the likelihood that a connection would be drawn between the goods and services for which the offending logo is used, and the NRMA, as a result of the well-known or famous nature of the NRMA’s registered marks.[12] The peculiar circumstances of this case were such that the derogatory use of the mark prevented the drawing of the requisite connection between the offending logo and the NRMA; it would be nonsensical for the NRMA attack itself.[13] This point necessarily flows on to the NRMA’s Australian Consumer Law claim, which is discussed in more detail below.

In dismissing the NRMA’s claim for trade mark infringement, his Honour did not provide any clarification on the NRMA’s argument that section 120(3) could be used as a specific anti-dilution mechanism.

Misleading or deceptive conduct

The NRMA claimed that a number of the representations made by the MUA about the safety of the NRMA-run ferries, the non-permanency of ferry employees, the wages paid to those employees, and the MUA’s use of the offending logo were misleading or deceptive.[14]

However, the claim was rejected on the basis that it was not enough for the conduct to merely be capable of affecting trade or commerce: the conduct itself must be in trade or commerce.[15] Griffiths J referenced how conduct associated with an existing employment relationship is not considered to be in the course of trade or commerce,[16] and by analogy held that neither could a trade union’s statements and logo use during industrial action about staff conditions and pay rates.[17]

In any event, Griffiths J did not find that the MUA had made misleading or deceptive representations by using the offending logo.[18] The context of use made it extremely unlikely that a reasonable person would be deceived or misled into inferring that the NRMA had licenced or otherwise approved of the offending logo’s use.[19]

Injurious Falsehood

The NRMA claimed that the MUA had committed the tort of injurious falsehood by way of its particular statements about the non-permanency of the employment offered by the NRMA to ferry staff and the wages paid to NRMA employees.[20]

In relation to the non-permanency statements made by the MUA, Griffiths J agreed with the NRMA in that those representations were held to be false.[21] However, the NRMA was still required to discharge the onus of proving malice.[22] For the tort to be made out, the court must find an “intent to injure…without just cause or excuse or by some…improper motive.”[23]

The injurious falsehood claim was ultimately dismissed on this basis, as not only could the NRMA not demonstrate an improper motive as the “dominant reason”[24] the MUA made the statements, but neither could it demonstrate that the MUA was recklessly indifferent to the truth or falsity of those statements.[25] His Honour also held that the use of the offending logo as a “hack” on the NRMA brand could not be used to contribute to a finding of malice on the part of the MUA.[26]

Key Takeaways

- Infringement of a registered trade mark will not arise if the offending mark has not been used as a trade mark, even if it is deceptively similar to the registered mark.

- Representations and use of logos may be deceptive but will not violate the Australian Consumer Law if the conduct is not in the course of trade or commerce.

- Statements may be false and injurious but will not be considered tortious at common law if there is no element of malice.

- The Australian Consumer Law may not assist an Applicant in circumstances where trade mark infringement cannot be established.

- The utility of Section 120(3) of the Trade Marks Act as an anti-dilution mechanism is still yet to be tested.

[1] National Roads and Motorists’ Association Limited v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union [2019] FCA 1491, [8] (NRMA v CFMMEU).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid, [9].

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, [15].

[6] Ibid, [49].

[7] Ibid, [65].

[8] Ibid, [102].

[9] Ibid, [114].

[10] Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), 120(1).

[11] NRMA v CFMMEU, [106].

[12] Ibid, [110].

[13] Ibid, [118], [119].

[14] Ibid, [52], [56], [61].

[15] Ibid, [133].

[16] Westpac Banking Corporation v Wittenberg [2016] FCAFC 33; 242 FCR 505.

[17] NRMA v CFMMEU, [135].

[18] Ibid, [181].

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid, [182].

[21] Ibid, [189].

[22] Ibid, [191].

[23] Ibid, [190],[192].

[24] Ibid, [198] .

[25] Ibid, [195].

[26] Ibid, [207].

Get the latest news insights and articles straight to your inbox, simply enter your details.